Within Canada and Quebec, maintaining global competiveness in a time of growing austerity, both in the public and private sector, and the bottoming out of neoliberal policies, has created a climate of insecurity. The continual scapegoating of migrant workers, immigrants, and those without status here in Canada hides the simple fact that neoliberalism can only exist on the backs of immigrant/migrant workers.

Yet at the same time the concentration of wealth in our society has become unprecedented. The 10 wealthiest people in Quebec have an equivalent wealth to the salaries of 1 million Quebecers working at minimum wage. Canada also has– quietly– one of the largest concentrations of billionaires on the planet, at 64. This level of wealth concentration– brought on by the neoliberalism of the last three decades– has led to unprecedented poverty. In Toronto in 2012, there were 1.12 million visits to food banks, the second highest level on recorded number. At least in Toronto, this is largely due to the fact that even having a 40-hour a week job at minimum wage is not an escape from poverty. According to a groundbreaking report based on Statistics Canada labour and income data, the number of working poor in Toronto “pouring coffee, cleaning toilets and otherwise toiling for low wages in office towers and factories is growing dramatically. Between 2000 and 2005, the area’s working poor grew by 42 per cent, to 113,000 people.”

The use of flexible labor, the attack on unions, and wages, has certainly been vital to the vast increase in profits and wealth for the few. This has been mainly through the creation of the “neoliberal” worker, driven by precarity through migrant and immigrant labour in three major ways:

The first and most critical: in Canada today there is an estimated 250,000-400,000 undocumented workers, mainly working for cash below minimum wage, in construction, hospitality, through forms of day labor and temporary placement agencies. The second, which has now become a new measure of permanent temporariness is the 300,000 Temporary Foreign Workers now in Canada which exploded since 2008. The third is the structural racialization of low wage work even amongst those workers who are landed immigrants or permanent residents. They make up not a nominal part of the working class but are very central to its functioning and the creation of a changing economy.

In a way migrant workers have become a central component of a neoliberal strategy to ‘internalize outsourcing’. What we are not seeing now is a further upswing in “outsourcing” of labor (which was so central to the economic crises of the seventies). Replacing that model is a drastic increase in the “in-sourcing” of cheap labour: in other words, rather than moving jobs to the global south, companies are in-sourcing immigrants/migrants here to be a cheap source of labor.

Just In Time Immigration!

Another aspect of this in-sourcing has been through a virtual regression in immigration policy instead of status for all, or full regularization Canada has made it virtually impossible to immigrate unless it is through a Temporary Foreign Worker Program so that now immigration will only happen on a very temporary basis and be tied to specific employers.

In a report released by the Metcalfe Foundation in 2012, the links between privately owned temporary agencies and the federally supervised TFWPs was made clear: “while the government creates the conditions which allow the migrant work relationships to be formed, the supervision of the relationship is increasingly privatized between employer and worker.”

Temporary Foreign Worker Programs bring migrants into the country for specific jobs on a temporary basis, meaning that a worker’s ability to continue to live in Canada is contingent on keeping the work they were brought to do. Unlike other paths to move to Canada (student visas, refugee claims, and so on) most TFWPs do not guarantee, or even offer, any path to citizenship or permanent residency.

This is the newest phenomenon in the larger neoliberal effort to restructure labour, with over 300,000 workers in Canada under the auspices of TFW programs (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2011). In fact, in just the last five years, 30% of all new jobs created in Canada have been to temporary foreign workers (Statistics Canada, 2012). As one might expect when one’s job is indelibly tied to one’s immigration status, the conditions created by these programs have led to what might well be described as a form of indentured labor. As a Temporary Foreign Worker, you are given a work permit that is tied to a single employer. If you are fired, you lose your temporary immigration status—a status that has in most cases already came at a high financial and psychological cost to the worker. The result is that workplaces are rampant with abuse, with many workers putting in 60 hours a week or more, for considerably less than minimum wage, with no holidays, vacations, or sick leave, and no ability to demand change.

Why Outsource? When you can Insource!

In Canada/Quebec the path towards working poverty through temporary underpaid work has flourished in recent decades. According to Stats Canada the increase has been an $8.7-billion revenue from the temp industry in Canada in 2009 (up from $1-billion in 1993). The number of workers in temp agencies has risen to 158,000 employed in temp services in the past year, up six per cent from the previous year. The earnings gap between a permanent and a contract worker is about 13 per cent, while between a permanent and casual worker the gap is about 34 per cent, according to Stats Canada figures. The disparity persists even after the agency adjusts for demographic differences like education levels, immigrant status and gender.

Temp agencies are strategic for employers in two critical ways. First, hiring workers through temporary agencies allows companies to completely escape even the most basic work standards. To begin with, the contractual nature of agency work means that workers lose access to vacation pay, overtime and seniority benefits. There is also no clarity within Quebec law on whether the agency or their partner company is the responsible employer, making it impossible, for instance, for a worker to fight an unjust dismissal, or a termination with insufficient notice. Furthermore, the industry is so unregulated that when an agency is charged through the Labour Standards Act, they are able to close their doors and open next door under another name. Effectively, labour standards do not apply. Secondly, the use of temporary agency workers allows companies to undermine collective bargaining and unionization efforts. This is primarily because companies are able to fire and hire temporary agency workers at will. In turn, this enables companies to change workers and inflate the numbers of workers so quickly and frequently that it would be impossible to achieve the “majority” needed to form a union. For temporary agency workers– who are often also undocumented, living with precarious status, or are refugee claimants– the nightmare of a crisis has become an everyday reality. These agencies operate mainly in the agricultural sector and food processing sector. Even large plants for Oasis juice, Mr. Basilic, just to name a few, use day labor agencies, where workers will wait in the morning in front of a metro station to see if there is work for that day outside of the city. This type of labor practice is more common in the U.S. but is now being used here in larger cities such as Montreal and Toronto. Employers pay cash at the end of the day. Most workers are paid below the minimum wage, with no access to any health and safety rights or basic respect for minimum labor standards.

In 2010 Enquette, an investigative journalism program on Radio Canada, documented the worst practices of “fly by night” agencies, by sending undercover journalists to work in different agencies as new immigrants. In one instance, the journalist wore hidden cameras when they applied to temporary agencies that specialize in placing immigrants who don’t speak English or French. Both men were assigned to Montreal chicken factories, where they worked alongside regular staff. “No one ever asked me for a single piece of ID. Not even my… [health] card. If I’d had a workplace accident, what would have happened then? Who would have been responsible for my care?” said Martin Movilla an undercover journalist. Movilla and Mendez were expected to work long shifts, up to nine hours at a time, sometimes with only one 15-minute break. They were paid between $6.50 and $8.00 per hour. The minimum wage in Quebec is $9.50.

Global Austerity -Montreal Style!

One particularly stark example here in Montreal of the neo-liberal restructuring that has occurred over the past thirty years is the Dollarama chain. Given the seeming impossibility of profiting off of items whose retail price never reaches more than 3 dollars, it is impressive that their CEO, Larry Rossy, is one of Canada’s 100 richest people; he is the 8th wealthiest in Quebec, with a worth of 1.05 billion dollars.

A rise in poverty across the country is one of the reasons that Dollarama does so well: people are forced to buy at one of its 700 outlets across Canada. A second reason that the pricing is profitable, however, is that Dollarama keeps their workers in extremely precarious and highly underpaid positions. Rossy calls this a “minimum wage strategy”, meaning quite clearly that if he could pay his workers less, he would. The Dollarama distribution centres here in Montreal employ anywhere between 500 to 1,000 workers—almost all non-white— who have almost entirely been hired through temporary placement agencies. Even the workers who have been there for several years are still considered “temp” workers, without benefits or pensions and with harsh working conditions. Ironically, the precarity of the work and the poverty level wages are exactly what makes it nearly impossible for Dollarama’s staff to fight for better working conditions. Without even considering the conditions in which Dollarama’s products are manufactured in the global south, the company is already a prime example of how the flexibilization has led to vast profits for Canada’s wealthiest. One worker from Haiti who after 17 years of work for Dollarama received a Christmas bonus of $45.00 bonus. In the same three month period Dollarama grossed $52 million dollars in profit, in 2011.

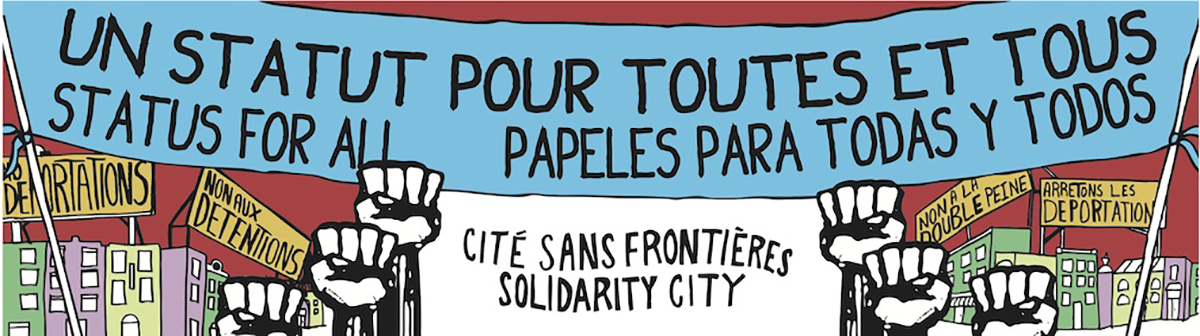

STATUS FOR ALL! LIVING WAGE FOR ALL!

In this climate of austerity and the increase of deportations, the changes to immigration go hand in hand. For capital, not only has the tool of austerity been repression through the billy club, but for workers, the policy of austerity is immigration policy. Fear is maintained within migrants through deportation, keeping migrants without status and without access to services in order to carry out their disciplining of labour, in order to stop them from fighting for decent work conditions and fundamental rights. This is why if we seek to fight austerity in all its forms the fight for full regularization is central, to lift the living conditions of all and to secure decent work with a living wage, not a poverty wage, for all.