(In early March, SAWCC community workers met to discuss what should go into this submission. The following is the result.)

Gender, race and class are integral to our experiences of migration and settlement. The SAWCC is a service, support and advocacy organization. Though our focus is women with origins in South Asia, we are there for anyone who seeks our assistance. We have a centre, active outreach programs and a lot of interaction with community organizations, umbrella groups of women, and coalitions that work in a variety of ways with immigrants and refugees. We are empowered by what we do and try to minimize distinctions and hierarchies of ‘client’ and ‘service provider’. From our start in 1981, we straddled different arenas. We don’t compartmentalize services, support and advocacy. For us they are a complete package. Our understanding is informed by our work and experiences as immigrants and refugees.

A key concern of ours has always been violence against women and so we know how women, especially in situations of precarity, are impacted on by their status as refugees or sponsored spouses. To maintain permanent residency, a sponsored spouse, and this is often how women of South Asian origin arrive in Montréal, has to live with the sponsor in Canada for two years. This makes a woman completely dependent on her husband for everything and places her in an unequal power relationship with her husband. If she needs to leave home for her own protection, or the marriage breaks down, she may no longer be permitted to remain. The fact that she may be sent back to her country of origin, something she may not wish for a variety of reasons, influences what decision she might make.

In most cases of domestic violence, irrespective of immigration status, women do not usually decide to leave their partner right away. Only after the growing realization that the behaviour will not change, or if children are endangered, does a woman usually decide to leave. Her options are greatly reduced when she is not ‘free’ to choose, because her status is based on remaining married to her husband and living with him. Other complications can also occur. We have seen how, when police arrived at a home in response to a call about suspected domestic violence, and the woman was unable to effectively communicate in English or French, her husband misrepresented what had happened; said it was a misunderstanding. He took all her documents, which complicated her struggle to remain here, while living apart from her sponsor. While SAWCC offers a lot of practical and moral support, we can’t escape the reality of vulnerability of women who come as sponsored spouses .

Our experience from other cases of marital breakdown, has shown us that a woman might feel a greater sense of autonomy here. As well, if she returns to her parents’ home in her country of origin, she might be seen as a ‘failure’ by relatives and neighbours. Over here, she could re-invent her life and live without that stigma. For the safety and well-being of women, we would like the sponsorship restrictions removed.

As the law stands, there is a lot of discretionary power that an immigration officer has. For example, in a different kind of sponsorship situation, if a woman arrived as a refugee and her claim was rejected, but in the meantime she had fallen in love and got married to a Canadian citizen or permanent resident, he could sponsor her for permanent resident status. However, if after her marriage, she was a victim of domestic violence and sought to leave her husband, her spouse could withdraw the sponsorship. She would be forced to return to the country she was fleeing from. If children were born of the marriage, and Youth Protection got involved because of violence, the mother could appeal for permission to remain, on humanitarian grounds. A new file would then be opened. If there are no Canadian-born children, the woman could still apply on humanitarian grounds, but only after one year had passed. In such cases, immigration officers have a lot of say in what happens. If a woman is deported before the end of one year, this could affect the eventual outcome for her.

Apart from crisis situations, we also assist immigrants and refugees more generally with settlement and employment. Seeking work without much success affects one adversely — loss of dignity, feeling depressed. More so for people who have come to a new country and often do not have local support networks. Immigrants often encounter hurdles to find work in their own fields. Among other things, the lack of ‘Canadian experience’ is a major handicap in this area. They find they have to settle for whatever they get. Economic vulnerability in a new country has resulted at times in unscrupulous employers exploiting the situation.

Even skilled workers who are fluent in French encounter difficulties. Many newcomers also find that their search for work receives a setback if they don’t know English. On arrival, there is the struggle to make ends meet, and often there is no extra money for language classes. At SAWCC, for many years, we have provided English classes, with the assistance of dedicated volunteer teachers. Many benefit from these classes and like other things offered at SAWCC, not only are they free of charge, but they are open to all women of any origin. Changes introduced by Québec’s Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities means that organizations like ours are no longer funded for any work we do on employability and refugee claims. While this does not stop us from helping whoever seeks us out, it demonstrates how governments are not in tune with the realities of the lives of newcomers; that organizations such as ours, that offer a complete package of information, support and referral are sought after.

There was the case of a woman who had come to work with a family who had recruited her from South Asia. She was brought by the family on the live-in caregiver program. She was isolated in her employer’s home where she had to look after an elderly relative. Living without any contact with anyone outside her employer’s home and finding her work situation exploitative, she was reduced to a very desperate situation. She finally escaped one day, but had to fight to remain in Canada. When she first escaped, we found a family should could live with.

At times, we work with women who are in immigration detention, pending deportation. We try our best to assist them but it is difficult, because often the women’s cases were compromised from the start by incorrect information and advice they got from lawyers and immigration councillors. If only they had contacted us earlier, the outcome might have been different. People fleeing political conflict, genocide and gender persecution often leave without much documentation. There is a whole process of negotiating the refugee process that is very fraught. We provide whatever assistance we can. Our concerns for our communities have also involved us in speaking out against unjust and discriminatory refugee and immigration policies and practices.

Women with young children who need to learn French can, like other newcomers, attend classes provided by the Québec government. But it has become more difficult. In the past, full-time on-site daycare was also provided. This is no longer the case. Parents have to find their own daycare. Though the government pays a stipend to parents for this, there aren’t enough daycare spots. Also, while government-funded French programs (full- and part-time) are open to those who have received a Québec Selection Certificate [CSQ] – accepted refugees, permanent residents and naturalized Canadian citizens, others, including people still awaiting a decision on their refugee status, and hence without a CSQ, can only attend a part-time program. The barriers compound the challenges towards becoming self-sufficient. Also, quite a few women who might wait for their children to start attending school, before they venture out to learn French and look for work, are adversely affected by the imposition of a five year limit. If this is the case, you are only eligible for part-time classes, unless you are a welfare recipient, in which case, even if here for longer than five years, you can avail of full-time classes offered by that ministry.

Recent changes in immigration laws make it harder for families to reunite. A refugee who gets accepted as a permanent resident is still entitled to sponsor her/his family, but now they have to wait five years. And during this period of separation, the person is not permitted to travel to her/his country of origin to visit the family. Sponsorship of parents and siblings has been stopped. The government claims that with the creation of ‘super visas’ it is relatively easy for parents to visit. But these visas are not easy to get. For refugees, the changes mean that no appeal on humanitarian grounds can be made before one year is up. In a recent case, a successful refugee claimant wanted to bring his mother and sister to Canada. They had to undergo very expensive DNA as well as bone marrow testing in their country. Even though this proved they were family, only the mother got accepted. The sister did not, and there can be no appeal of this decision.

Non-status people are not entitled to any services, even healthcare. The only caveat is if an individual has a serious communicable illness that can spread to the larger population. Cuts to welfare payments, that are already much lower than what is required to remain out of poverty, as well as the tightening of employment insurance access, negatively affect our communities. School boards do not allow children of non-status parents to register for school, institutionalizing inequality.

Changes in the citizenship process means applicants for this must now prove competence in either English or French. They must undergo testing for language proficiency at centres approved by the government, at a cost of $250. After that, there is still the citizenship test that one has to pass. Also, the new preparation booklet for the citizenship exam is very difficult. We help people prepare for this.

We offer many services to assist newcomers to Montréal, Québec and Canada. We assist individuals and families access their child tax benefits, old age pensions and family allowances. If there are legal needs we connect people with lawyers or legal aid.

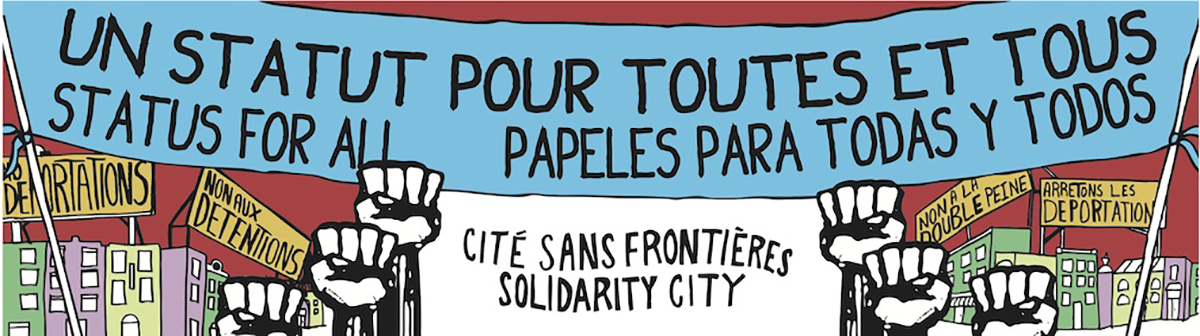

Due to our work with other service provision organizations in the wider Québec community, we have been able to sensitize them to some extent to our realities in terms of gender, race, class and immigration status. We also collaborate with many of them in areas such as cutbacks in healthcare, transportation fare hikes, and violence against women. Our contribution in building awareness in these organizations has helped in increased solidarity with migrants, refugees and non-status people. We also work with other migrant justice organizations to protest and challenge the injustices of refugee laws, the politicized targeting of minority communities that threaten many with deportation, and the climate of fear and insecurity where immigrants, refugees and non-status people are encouraged to denounce community members. We inform people in our communities of their rights and the strength that comes from working in solidarity and breaking isolation. Laws that create a climate of fear and insecurity should be abolished. What we would like to see is a liberalized immigration policy, families to be reunited, and the removal of sponsorship liability which places women’s lives in danger. Canada should provide a safe haven for all those seeking refuge from political and gender danger. Specifically in Québec, everyone should be entitled to medical care and all children should be able to attend school. Our experience has shown us that working together in our communities and in solidarity with other communities and organizations that share the same goals as us, gives us strength with which we can make positive change.