This article, by members of Solidarity Across Borders, is featured in the Printemps 2015 newspaper. More info here: grevecontrelausterite.

Austerity is often described as an act of class war, on the part of the rich. Depending on who is talking, this assault might be described as an attack against the middle class or the working class, or any number of constituencies in capitalism’s gunsights. It affects many people; consequently specific examples can galvanize broad opposition, mass mobilizations, and … easy recuperations. Because while neoliberal austerity hits many people, it does not hit us in the same way, nor with the same force.

Austerity appears to some as a theft, robbing them of the standard of living that they and their families worked so hard to attain. For others, austerity appears as a giant step backwards, with the hard-won victories of previous generations rolled back and lost. There is often an uncritical appraisal of capitalism before neoliberalism, and of who really paid for those hard-won victories and higher standards of living in years past. The politics these perspectives give rise to are conservative, literally: wanting to conserve what people had before the cutbacks, the privatizations, etc.

Such politics often blame austerity on corrupt politicians, strange conspiracies, foreign interests, and a specifically “globalist” capitalism. Their solutions tend to be reformist, nationalist, pro-State. Ultimately, they aim to negotiate a better deal with capitalism.

Canadian Capitalism

In the northern half of Turtle Island, contemporary capitalism is based on four main axes:

- Dispossession of Indigenous peoples on territory claimed by the Canadian State, largely in order to extract resources from their lands, but also for development. For instance, the tar sands in Alberta, Energy East, and Plan Nord here in Quebec. It is important to remember that Canada’s entire model of development and capital accumulation is predicated on the subjugation of these Indigenous nations. It can’t happen otherwise.

- Dispossession of peoples around the world, to rob them of their resources. Nearly 80% of the world’s mining companies are based in Canada, their operations often leaving social and ecological devastation in their wake. This is particularly brutal sector; for instance, the Vancouver-based Pacific Rim Mining Corporation has been implicated in the murder of opponents of its activities in El Salvador.

- Superexploitation of workers in the Global South. For instance, in 2013 the Quebec-based company Gildan Activewear enjoyed net earnings of $320 million. 41,000 workers created these profits, all Gildan sweatshops being located in the Global South: Honduras, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Bangladesh. The daily wages for these Gildan workers is often less than the hourly minimum wage in Canada. Such superexploitation builds on the legacy of colonial slavery, white supremacy being the foundational ideology of North America.

- Keeping Canadian and Quebec workers loyal to capitalism, both through maintaining their privileges over other workers, and by encouraging racist and xenophobic mobilizations in defense of these positions of privilege. Although these “privileges” are largely illusory for some, an identification with Canada, Quebec, and “whiteness”, and the associated First World standards of living, binds even highly exploited and precarious sections of the population to the capitalist nation-state; as a privileged status (no matter how inaccessible) appears as the “norm”, failure to receive this status leads to a search for scapegoats (immigrants, crooked politicians, Indigenous peoples, etc.) rather than a rejection of capitalism per se. Under neoliberalism, using bribes to get the loyalty of more privileged workers will become increasingly difficult, as the expense hampers Canada’s international competitivity. Without political intervention from anti-racist, anti-imperialist and anti-colonial forces, when nationally privileged workers rebel against their fate under capitalism they face a strong tendency to adopt the kind of conservative politics mentioned above, often with a racist edge.

Immigrant and Migrant Workers in Canada: A Snapshot

As author David McNally has observed, “It’s not that global business does not want immigrant labor [in] the West. It simply wants this labour on its own terms: frightened, oppressed, vulnerable.”

In lockstep with the consolidation of neoliberal austerity, economies throughout the Global North have come to rely increasingly on immigrants and migrants. The goal is to have access to hyperflexible low-cost labour: use-up-and-dispose workers, people to be exploited and then sent home, without any possibility of accessing the oppressor-nation privileges their labour has helped maintain. Coming from societies in the Global South which have been devastated by (neo-)colonialism, for many of these people austerity is not something new, just more of the same. The services and resources being cut back were often designed to never be accessible to them in the first place.

In lockstep with the consolidation of neoliberal austerity, economies throughout the Global North have come to rely increasingly on immigrants and migrants. The goal is to have access to hyperflexible low-cost labour: use-up-and-dispose workers, people to be exploited and then sent home, without any possibility of accessing the oppressor-nation privileges their labour has helped maintain. Coming from societies in the Global South which have been devastated by (neo-)colonialism, for many of these people austerity is not something new, just more of the same. The services and resources being cut back were often designed to never be accessible to them in the first place.

It is no coincidence that the first temporary work program was created in 1966, just a few years after the explicit racial categories that had previously defined immigration law in Canada were removed. The Non-Immigrant Employment Authorization Program (NIEAP) created a distinct category of “low-skilled” workers, the majority of whom would come from the Global South. It took some years for NIEAP to fully come into its own, but by the 1980s, temporary employment authorizations had eclipsed the number of workers permitted entry on a permanent basis.

In parallel with this, the class trajectory of even permanent immigrants to Canada began to change. A majority of immigrants, even those who were middle class in their country of origin, were now funneled (by mostly informal racist mechanisms) into the most exploited and precarious jobs. As such, structural racialization of low-wage work persisted even amongst “new Canadians”. (At the same time, a privileged section of these immigrant communities has been integrated into the multicultural middle class and worker elite. This immigrant middle class is squeezed between its own contradictions with settler-colonialism (dealing with racism in addition to the same neoliberal pressures as the rest of the middle class) and the role it plays politically binding the precarious immigrant working class to the neocolonial project – or at least neutralizing its opposition.)

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) was established in 2002 as an outgrowth of the NIEAP. It has rapidly expanded, tripling since 2006, further signaling the centrality of this hyperflexible workforce to capitalism’s plans. Employers are able to source labour from any country around the world without government oversight or bilateral agreements. There is no path to permanent residency; workers’ right to remain in Canada is tied to their employer. Most migrant workers return year after year to complete the same “short-term,” exploitative contract job.

These workers have been “permanently temporary”, locked into a situation of persistent insecurity. However, changes due to come into effect on April 1, 2015, will make their situation even worse. The new “4 and 4” legislation, targeting the most highly exploited workers in the TFWP, will limit these people to working four years and will then bar them from re-entering the country for the next four years. This is intended to make workers even more isolated and vulnerable, ushering in a system of revolving-door immigration for the most exploited. All low-waged temporary workers as well as migrants employed under the Live-In Caregiver streams who have worked in Canada for more than four years will be banned from working and forced to leave – one of the largest deportations in Canadian history. Eventually, over 60,000 people currently living in Canada (and hundreds of thousands more who will temporarily replace them) will be deported, forced to leave, or confined to surviving here as criminalized undocumented workers.

In addition to the 300,000 migrants working under the TFWP, there are currently an estimated 250,000-400,000 such undocumented immigrant workers in Canada. These people mainly work for cash, often without access to minimum wage, social assistance, or any basic labor protections. They constitute the most highly exploited section of the working class in this country.

While the Canadian State seeks to expand this hyperflexible migrant sector, it has simultaneously moved to restrict paths of permanent migration. As Harsha Walia of No One Is Illegal recounts,

“According to Avvy Yao-Yao Go, Director of the Metro Toronto Chinese and Southeast Asian Legal Clinic, ‘Thirty years ago, family-class immigrants made up the majority of all immigrants. Today, they account for less than 20 per cent of the total intake.’

“The Conservative government has instituted a quota of 5,000 applications (note, not acceptances) on the sponsorship of parents and grandparents. This comes after a complete two-year moratorium on reunification with parents or grandparents.

“In order to even qualify, the government has imposed stringent income requirements and families have to sign a 20-year financial undertaking. This means that for two decades sponsored parents and grandparents cannot access social assistance without returning it.”

Changes to family reunification are part and parcel of a series of government attacks against “undesirable” immigrants. Following the implementation of the Orwellian “Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act” (Bill C-31) in 2012, refugee acceptance rates were the lowest in Immigration and Refugee Board history, at 33%. In 2013, there were more than 15,000 deportations – over 40 a day – and over 9,000 people were caged in immigration prisons between 2012 and 2013. The government’s announcement in December 2014 that it was lifting the ban on deportations to Zimbabwe and Canada’s neocolony Haiti – because the situation in those countries has “improved” – means an additional 3,500 will face potential removal. (This underscores the hypocrisy of the global apartheid system: these two countries, now judged safe to deport people to, each remain subject to government travel advisories warning that they are unsafe for Canadian tourists.) Meanwhile, also in 2014, Bill C-24 became law, making it possible to revoke citizenship from dual nationals or even from Canadian-born children who have the possibility of accessing dual citizenship. In a shocking precedent, as a result of a minor non-violent criminal charge, Ottawa-born and Canadian passport-holder Deepan Budlakoti is facing expulsion to India, a country he only ever visited briefly when he was 12. It is a deportation frenzy.

Oppressor-Nation Racism

The effect of highly exploitable migrant labour on the nationally privileged workforce is complex. In some cases temporary foreign workers can act as a buffer maintaining higher wages, cheap services, and exemption from particularly hazardous or arduous jobs for Canadian workers.

At the same time, temporary workers can be used as part of the push to lower wages of these same historically privileged strata, by restricting their bargaining power and keeping business costs low. As we have seen, in this context some sectors respond with a conservative reflex, simultaneously racist and anti-austerity. Conservative anti-austerity politics concerned with saving “our” jobs and “our” way of life, serve as capitalism’s loyal opposition. They are not at all incompatible with the process of more forcefully policing the race and class borders of Canadian and Quebecois national identity – both on the level of discourse and politics and on the concrete level of police, courts, and prisons.

Both government and civil society actors have repeatedly encouraged and pandered to popular racism, using this bigotry as the white glue to bind oppressor-nation workers to “their” State. For instance, the Alberta Federation of Labour recently organized a protest against jobs on a public project being given to temporary foreign workers. “Most citizens would rather see their tax dollars going to their neighbours than being sent out of the province and out of the country,” Edmonton and District Labour Council president Bruce Fafard explained.

Such “us first” xenophobia is by no means confined to Alberta. Indeed, one of the worst examples of recent racism occurred right here in Quebec: the PQ’s Charte des valeurs québécoises. In the context of the 2012-3 “Charter debate”, countless acts of violence and harassment were directed at groups stigmatized by their adherence to specific “foreign” religions. The primary targets throughout were Muslims, especially Muslim women, who were accosted while taking the metro or walking down the street, insulted, told to “go home”, and physically assaulted, often by people trying to forcibly remove any head covering they were wearing. One informal online survey of Muslim women in the province in December 2012 found that of 338 respondents, 300 said they had suffered verbal abuse since the Charter controversy began.

Two years later, Islamophobia persists as a significant current in both Canadian and Quebecois political discourse. In February 2015, the Bloc Quebecois released advertisements aimed at NDP voters, attacking that party’s defense of the right to wear the niqab at citizenship ceremonies. At the same time, a Montreal judge barred a woman from her courtroom because she would not remove her hijab, and an opinion poll was released showing that 64% of people in Quebec would oppose a mosque being located in their neighbourhood.

Whether it is the Islamophobic Charter and rabblerousing, the deportation frenzy, or mobilizations to keep “our” jobs for “us”, what is on display is a white supremacist society, dependant on Third World labour, seeking to maintain its cultural, psychological, and economic dominance through violence and intimidation.

The Reproduction of Labour

Capitalists seek to extract the maximum labour from each worker, at minimum cost; for capitalism a worker is her labour power, and nothing more. The “permanently temporary” migrant worker suffers extreme forms of exploitation as capitalism pursues this ideal. The “temporariness” is key here, as it translates into massively reducing security and access to services or benefits outside of work, regardless of how many years one has laboured here.

Canadian employers are able to use such workers without bearing any of the costs of raising them, educating and training them, supporting them when they are sick and when they become elderly, or providing for their children or other dependents. The costs of reproducing this labour force are pushed out of the oppressor nations, relegated to workers’ communities and families in the Global South. Meanwhile, within Canada, non-status people are frequently denied access to healthcare, schooling, and other social services. Indeed, even non-State services, for instance many food banks, often refuse to provide assistance to people who are unable to provide the proper “legal” identification.

Such exclusion is frequently experienced as a hardship not only by the people directly affected, but also by family members who do what they can to step into the vacuum. In the Global South as in the Global North, such work often falls on women, as grandmothers, mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters do what they can to step in and care for their family members in distress.

That such feminized “reproductive labour”, both within Canada and offset onto the Global South, is either poorly paid or not paid at all, constitutes a source of superprofits that is as great as it is hidden.

Furthermore, migrant women in Canada suffer all of the same forms of exclusion as men, while also facing specific forms of gendered violence and oppression. In each regard, Canadian racism and sexism exacerbate the oppression and exclusion in question. For instance, as of August 2014, spouses must now arrive on a two-year conditional probationary visa before gaining permanent status, a fact which increases the vulnerability of immigrant women in abusive relationships as it makes their legal status contingent on staying with their partners. Further, under white supremacy, racialized and Indigenous women, queers, two-spirit, trans, as well as all those that fall beyond patriarchal gender and class norms, bear the brunt of capitalist and colonial violence. Within this, Canadian law enforcement itself remains a significant source of violence.

Finally, as shown in the case of the Quebec Charter of Values, women perceived as “foreign” are prime targets for racist violence and patronizing regulation. In the current period of heightened Islamophobia this is a particularly intense reality for Muslim women, who are simultaneously characterized as uniquely oppressed and uniquely dangerous. However, all women deemed “other” – not only immigrants and Muslims, but also (depending on circumstances) Indigenous women, poor women, sex workers, transwomen, and others – are vulnerable to such hate campaigns, which serve to keep them in a position of insecurity, just as they serve to bind (other) oppressor-nation women more tightly to their “own” patriarchal structures.

The Exclusion of the Atypical

Capitalism promotes the belief that only those who can “function” and be “independent”, who can fit in easily with the physical and emotional requirements of capitalist society, are “normal”. Never mind the fact that none of us consistently manage to do this, and that all of us for significant periods of our life (such as infancy and old age) require greater degrees of care. Such unreal ideas of what is “normal” are prevalent and rarely questioned. Our ideas and strategies and politics and anti-capitalism are then built around the “realities” of such fictitious non-existent “normal” people. This is one aspect of a system of oppression that can be referred to as “ableism”.

Amongst other things, ableism obscures a particularly vicious way that capitalism offsets labour costs, excluding and invisibilizing people beyond their capacity to work: neoliberal capitalism’s relationship to those whose bodily, mental, or emotional situations make them “unprofitable”. Bureaucratic definitions of “disability” are modified for maximum profitability. That this reveals disability, like gender, to be a social construct, should not come as a surprise. Indeed, there is a lot of overlap between the concerns of people with different disabilities, elderly people, children and infants, and people in crisis, dealing with trauma, and other major hardships in life.

That people have different requirements which can change within their own lifetimes, and that meeting these requirements is the responsibility of us all, is anathema to capitalism. Even for oppressor-nation citizens, various obstacles – lengthy paperwork, medical tests, doctors’ biases, incompetent assessments, misrepresentation – combine to deny or discount the needs of the disabled. Persons with disabilities are dehumanized and made to feel they are not as good as other people. This bad situation is kaleidoscopically worse for immigrants with disabilities.

The 1976 Immigration Act excluded people from Canada if a medical officer deemed them to be a burden to health and social services. The 2001 Immigration and Refugee Protection Act actually made things worse, by establishing explicit restrictive guidelines based on probable cost over a five and ten year period. The only possible way someone with a disability can legally immigrate to Canada is by claiming refugee status, a status that is getting harder and harder to get, or to fight in court to prove that family members have the financial means to care for dependents and are willing to do so. Otherwise disabled immigrants are rejected as a burden to be kept out of the country, entirely excluded from permanent residency. They are deported and their families can also be deported.

Care for people whose needs are not met by the neoliberal State falls first to parents and other family members, most especially women, who often must give up working in order to do this – a particularly heavy situation for immigrants who must prove financial independence or else face deportation. Of course, not everyone has family members able or willing to provide the care needed. In a society where one is denied access to services based on one’s citizenship status, disability can thus lead to homelessness and incarceration, to be followed by deportation.

Anti-Austerity or Anti-Colonialism?

Capitalism has always involved cutting deals, elevating some people to positions of power and dominance over others. Austerity is a favoured programme for the capitalists, but it is neither their only option nor is it essential to the survival of their system. An anti-austerity framework that is not anti-capitalist simply amounts to a demand that some people be treated better, be amongst the winners, that they get a good deal – never mind if that deal is at the expense of someone else.

Opposition movements have been deeply affected by pro-capitalist biases, even when they claim to be anti-capitalist. These biases can take the form of support for various kinds of reformed capitalism, for social democracy or “progressive” nationalism. For better deals. They can also work insidiously, with people simply overlooking certain questions, and thereby excluding them from their analysis. An ableist bias keeps issues of disability peripheral to its analysis, in the same way as a racist bias keeps issues of migrant workers peripheral to its analysis, in the same way as a sexist bias keeps issues of gender violence and reproductive labor peripheral to its analysis. This is not an exhaustive list. And each of these analytic oversights lays the foundation for real-world marginalization, the retrenchment of lines of division and exploitation both within society and our movements themselves.

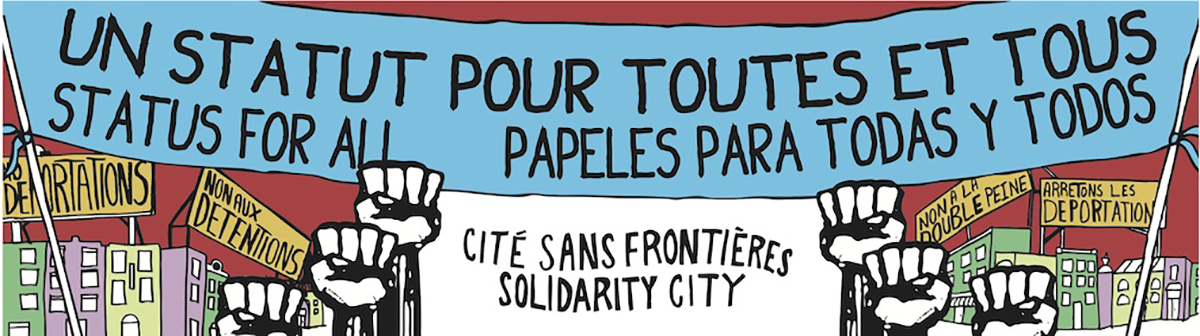

As we enter another period of struggle against austerity, we must intervene to make sure anti-racism, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism – as well as opposition to all forms of oppression – are the basis of any mobilization.