In December 2012, interviews were conducted with individuals working in organizations that provide primary health care to undocumented migrants in Montreal and Toronto. The interviews contributed to a document geared towards the use of the participant and ally organizations in order to learn what acts of resistance are taking place in clinics to fill the gaps of the Canadian health system, what the shared barriers are, and what tactics are used to overcome the barriers. This article does not touch on the countless barriers for those directly affected by Canada’s discriminatory healthcare system, but rather illustrates the periphery struggle of providing alternative healthcare services that are accessible to all.

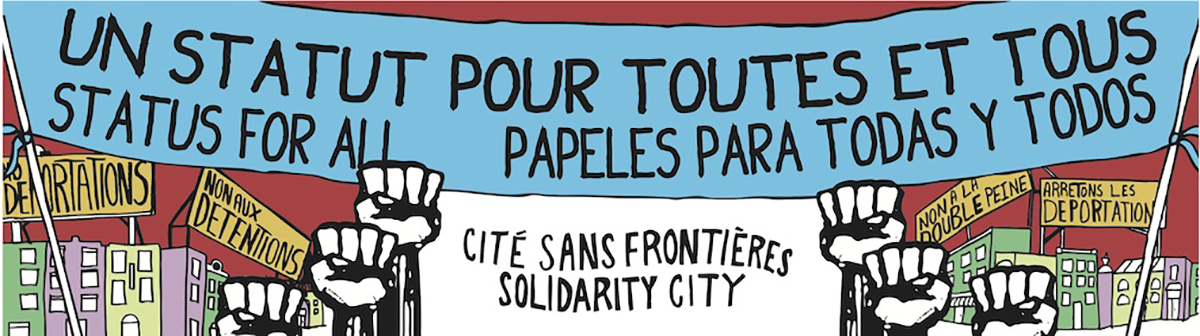

Countless people are denied access to healthcare in Canada. In Montreal alone, upwards of 50,000 people with precarious or no status are barred from accessing basic healthcare, including neo-natal care, basic check-ups, blood tests, and access to vital medications. The numerous individuals and healthcare practitioners who strive to fill this crucial gap mostly work voluntarily without the necessary resources to provide adequate care that everyone is entitled to. Despite the remarkable work of many community members, these programs and clinics continue to exist within a broken and racist healthcare system that stems from Canada’s colonial history. Clinics and healthcare providers should be pressured to refuse to abide by discriminatory policies that deny people necessary care.

In addition to numerous acts of resistance by those directly affected by the health cuts and those in solidarity, some healthcare practitioners are also resisting the shameful and exclusionary health policies of the Canadian government by advocating for policy change and providing care to migrants regardless of status. There are approximately eight programs in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver collectively that provide primary healthcare services to undocumented migrants. In addition, a few community clinics in these cities occasionally accept patients without asking for documentation and other organizations provide further health services such as counseling or dental work accessible to undocumented migrants. However, these programs are often underfunded and over-capacity, while community clinics regularly deny patients without documents even if they fall under the clinic’s mandate to care for people within a certain target group or geographic area.

These organizations face common barriers when providing primary care to undocumented migrants, as well as strategies to working around a failed system. The research draws from two community clinics and one student-run clinic in Toronto, as well as two programs run out of larger organizations in Montreal.

In many cases, primary care is not enough; referring patients to hospitalization and specialized care, such as blood work or radiology, proved to be a problem for all the organizations. Hospitals usually demand payment upfront before admitting undocumented patients unless they are in immediate life threatening conditions, in which case payment is required afterward. Referring patients to specialists or hospital treatment is a huge and common challenge that often requires turning to informal connections with practitioners in order to access specialty or hospital services. Also, sufficient medication and medical equipment is nearly impossible to obtain, which leads all the organizations to rely on basic sample medications and donated equipment to meet some patient needs. Evidently, these temporary strategies are unsustainable and do not allow patients to access adequate, dignified health services.

In volunteer clinics, consistency and proper follow-up are often challenging to ensure due to the nature of a rotating pool of volunteer practitioners. Patients must often re-explain their medical concerns to a new practitioner at every visit. Further, providing adequate care and understanding the health issues of each patient is nearly impossible due to inconsistent or nonexistent health records. These issues are problematic in that such inconsistency cannot produce reliable results. Practitioners noted repeatedly that they were not able to provide the necessary standard of care that they would otherwise provide to their insured patients. The undeniable discrepancy in care depending on legal status is unethical, dehumanizing and creates tiered healthcare access.

Many individuals and organizations have developed methods to lessen the barriers to providing for undocumented patients, though they are neither sustainable nor acceptable as a substitute for holistic healthcare access. Some organizations established emergency funds allocated to expensive medications or services that are critical and normally unaffordable. Two clinics have developed payment plans with hospitals, which may take the form of multiple payments over a period of time, reduced fee costs, or other negotiations. One of them also signed a contract with a hospital to request the hospital fees for undocumented patients be reduced and therefore equivalent to that of patients with Ontario health insurance. Despite these efforts, such negotiations are short-term “solutions” in the face of desperate healthcare needs that are otherwise not met.

Cultures of racism and xenophobia fostered by the Canadian government prevent organizations from being public and outright about providing access to undocumented migrant people. No interviewed organization providing primary care to undocumented migrants mentions the politicized terms “non-status” and “undocumented” in their names or publications often in order to avoid ideological opposition and to protect their funding. As a result, the organizations must limit their promotion, as well as balance advocating healthcare access for all, while maintaining government funding. Such an environment of fear contributes to the criminalization of migrant people who live, work and contribute to our communities. The Canadian government has made clear its anti-migrant agenda with the cuts to the Interim Federal Health Program and the introduction of the Refugee Exclusion Act (the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act, Bill C-31), which is an extension of Canada’s colonial history of exclusionary and racist immigration policies.

In the process of providing health access for all and services for all regardless of status, community clinics should take immediate steps forward by refusing to cooperate with Canada’s exclusionary health policies and accepting all patients regardless of status. Practitioners in community clinics are most often paid on salary; in other words, their patients do not affect their funding for the most part, which makes room for the flexibility to provide for anyone and everyone. However, many community clinics continue to demand documentation and actively create an environment that is openly hostile to migrants. Resistance is necessary to combat attacks by the Canadian government, which exploits, commodifies, and benefits from countless undocumented people. Community clinics need to be pressured to accept all patients regardless of status in order to temporarily fill the immediate gap that puts the lives of thousands at risk.