The situation of non-status migrants

Non-status migrants, along with temporary foreign workers, are among the most exploited. Their existence – estimated at around 40,000 in the Montreal area – creates a fundamentally unjust reality in the heart of our community, one where certain individuals have access to fundamental rights and services – such as education, healthcare and labour regulations – while others don’t. Those who do not have status, or do not have full status as a resident, can be exploited more easily since they live in fear of being detained or deported. These individuals often live in fear, anxiety and isolation.

This human and social reality is not a bureaucratic error that will resolve itself – it is just the opposite. States have a tendency to considerably tighten their immigration and refugee policies and to reduce the opportunities associated with these policies. States like Canada are following a global trend of tougher border controls by shamelessly using repressive techniques and policies such as detention and deportation or by limiting access to residency and citizenship using discriminatory and hyper-selective criteria. This closing of borders pushes an ever-increasing number of migrants towards perilous journeys or non-official residency and towards legal and social exclusion which violates national standards and States’ international obligations of human rights.

Even if some benefit from the opportunities that it offers, the present immigration system has become, for so many others, a machine whose role is to create irregular situations, human and social vulnerabilities, and categories without the most basic rights. We are convinced that the only solution to these unjust situations is the total elimination of a lack of national status. We are therefore demanding the complete and continual regularization of all non-status migrants.

Not having access to education: a scandalous and unacknowledged discrimination

Thousands of children living in Quebec do not have access to education. They may be non-status migrants like their parents, or born in Canada to parents without status, or children of rejected asylum seekers or of foreigners awaiting deportation. All of these children are barred from the fundamental right that is education.

Parents that go through the bureaucratic enrolment processes face a multitude of obstacles often condemning their children to exclusion from the education system. For example, families who cannot provide the papers required for the enrolment of their children (health insurance card, birth certificate, etc.) are refused access to education institutions. The climate of suspicion and repression towards non-status migrants can also make whole families live in fear. Fearing detention and deportation, these families hesitate to enrol their children in school.

While certain schools accept children if they pay the tuition fees. This cost, however, which can reach to $6000, effectively exclude poor families. The lack of clear regulations regarding access to education for these children causes discriminatory and scandalous situations under the discretionary power of administrators.

Being barred from education translates to social isolation for these children who have already had to deal with complicated journeys and hardships. This social exclusion can have regrettable long-term consequences: everyone knows the importance of school for individual development, social and cultural formation, and integration. Furthermore, late enrolment can also permanently impede school and personal progress.

This discrimination also affects children before (access to child care services) and after mandatory elementary and secondary education. For young adults, accessing professional, skill-based, collegial and university programs as non-status migrants is mired with obstacles. Before issuing a diploma, the Quebec Ministry of Education requires a student to have a permanent code, which can only be obtained with proof of legal status. This discriminatory practice pushes non-status migrants to abandon their studies since they will not receive a diploma validating their studies.

Our demands

We demand the following:

1. that all migrants have access to public schooling regardless of their immigration status

2. that everyone, regardless of their immigration status, have access to free public schooling, from kindergarten to university. We therefore support the efforts against tuition hikes and for free and accessible education.

Some cases

Born in the Caribbeans, Max is 12 years-old. He joined his mom who immigrated to Canada 3 years ago. After a number of refusals from school principals and school boards because of his lack of status, a school accepts to enrol him only if his family pays expensive tuition fees. His mom, who is a house cleaner, cannot afford the fee, forcing Max to stay home alone often. Receiving refugee status 2 years later, Max can finally enrol in school but he has numerous difficulties because he is two years behind.

In 2005, Vlad was 13 years-old and moved to Canada from Russia with his family. Not being able to enrol in a public school, his parents have to pay expensive tuition fees at a private school. Since he does not have a permanent code from the ministry of Education because he does not have status he will not receive his high school diploma. Now as a permanent resident, Vlad is faced with the impossibility of enrolling in a CEGEP since his high school diploma was never issued.

Rosa is 14 years-old and from Mexico. She was refused her refugee status. In August 2009, she receives a deportation order along with the rest of her family. While waiting for the deportation scheduled for January she would like to enrol in school but she is refused this 4 month-long enrolment.

Education is a right

Education is a universal and inalienable right whose recognition is the basis of freedom, justice and peace in the world. The right to education is enshrined in many international human rights protection instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

The international instruments state the following:

- The right to education is recognized to all without discrimination

- Elementary education is mandatory and must be free

- Secondary education, including skill-based and professional programs, must be widespread and made accessible to all

- Access to higher education must be open to all equally

- The right to education must be given without any distinction to national origin or any other situation

Canada ratified all of these instruments and is bound to the principles of the Universal Declaration. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act protects the right of all children to have access to preschool, elementary and secondary education, except those of temporary residents not authorized to have employment or study. The Quebec Education Act recognizes that these services must be free.

However, individuals in irregular situations face obstacles in accessing education. Canada is under the obligation to conform to international obligations and to enforce the right to education for “all”, regardless of their immigration status.

The Right to Education in other countries: Better Protection and Practices

Many countries have laws and bureaucratic processes that protect the right to education for individuals in irregular situations.

In the United States, schools cannot refuse access to children because of their immigration status. Since a 1982 ruling of the Supreme Court, barring a child’s right to free education is a violation of “equal protection under the law” protected by the Constitution. Twelve states, such as Texas, California, New York, Utah and Illinois, voted laws that allow students without status to have access to assistance programs and reduced tuition fees. In Europe, Belgium, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands all explicitly recognize the right to elementary education for children in irregular situations.

In Germany, access to education is protected in Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia.

In Sweden, children of rejected asylum seekers can continue their schooling until the execution of the deportation order. Municipalities have the power to enrol non-status children in schools.

Access to education for non-status individuals is encouraged in certain countries. In Portugal, attending preschool, primary school, secondary or professional education is grounds for the legalisation of minors born in Portugal

No documents are required for enrolling in school in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and in some German Länders.

In Spain, underaged non-status migrants can benefit from scholarships and social assistance to help cover the cost of tuition. The Netherlands also allocates money towards similar ends.

The Education Without Borders Collective

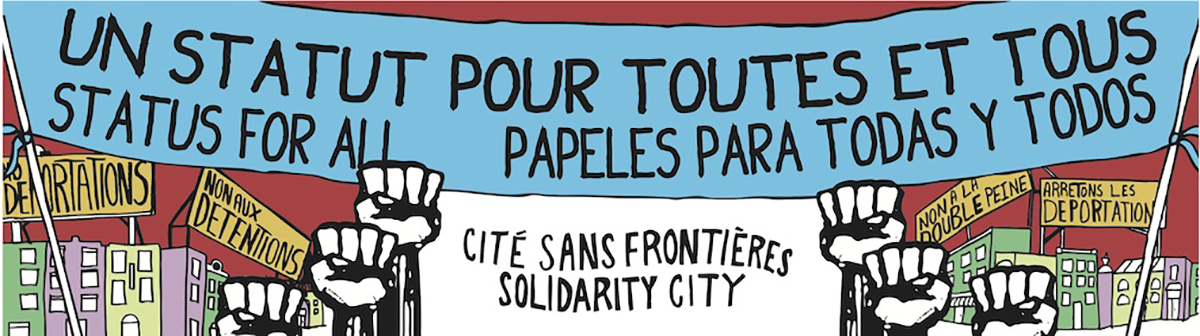

Formed in the fall of 2011, the Education Without Borders Collective is made up of migrants and their allies – parents, students, researchers, activists – concerned with the exclusion of children from public education because of their immigration status. This collective is linked to Solidarity Across Borders (SAB), a network involved in migrant struggles since 2003, demanding the regularization of all non-status migrants, an end to detentions, deportations and double punishment. The collective sprang up from the “Solidarity City” campaign (spearheaded by SAB) which aims at making Montreal a city where anyone, regardless of their immigration status, can have access to essential services such as free healthcare (in hospitals, clinics and CLSCs), education, social housing, food banks and shelters for victims of violence.

Do you support our demands?

1. Contact us, whether you want to get involved or if you just want to stay informed.

2. Read, sign (as an individual or an organization) and forward our collective declaration (www.solidaritesansfrontieres.org).

Together, let’s build a struggle to pressure the institutions to give in to our demands and to eliminate the injustice of living without status.