Three women, three different circumstances

All names have been changed to protect the confidentiality of our patients.

Yousra. Living in Canada for almost two years, Yousra is still waiting for the decision on the sponsorship application submitted by her husband which will give her permanent resident status. As her immigration file has not yet been processed, her unplanned pregnancy has her worried that she will not be able to afford the medical attention she needs, and that she will be refused services at the hospital.

Anna-Maria. Anna-Maria fled her homeland fearing for her life, and will never return. Her asylum application and her application for residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds were refused. Having already exhausted all possible methods of attaining legal status, she has been living in Montreal with no status for over six years. Five months pregnant, she has received no medical attention and she fears that when she goes into labour, she will be turned away from the hospital.

Marie-Josèphe. As her husband has been working in Canada for a few years, Marie-Josèphe decided to come with him to Montreal on a visitor’s visa in the hope of one day moving to Canada for good. Ten weeks pregnant, she knows that it will be extremely difficult to pay for the medical attention she needs, but she does not want to consider terminating the pregnancy.

Insecure access to maternal health care

Yousra, Anna-Maria and Marie-Josèphe are only a small fraction of the women whose precarious immigration status does not allow them to access pregnancy care and childbirth in hospitals. In fact, thousands of women living in Canada have precarious immigration status, or no legal status at all. These women are ineligible for Quebec’s provincial health care system and for the Interim Federal Health Program, and are therefore billed for all the health care they receive.

In Quebec, the cost of health care is exorbitant for anyone without a valid health card. A simple medical appointment can cost as much as $200; on top of that is added the cost of blood tests, ultrasounds and any other tests required to ensure the health of the mother and child. The average bill for childbirth services ranges from $7,000 to $10,000 depending on the institution, but fees are often higher if there are complications, or if more complex medical attention is needed. This amount includes the hospital fees for the mother (between $2,500 and $3,500/day, depending on the hospital) and the baby (between $1,000 and $1,500/day), as well as the physician’s fees (between $1,500 and $3,000). For women who need it, an epidural adds from $500 to $900 to the bill. These exorbitant costs are a direct obstacle to health care services that are essential to maternal health.

The nurses at Médecins du Monde receive calls every week from pregnant women without medical coverage, overwhelmed by the exorbitant costs charged by the clinics and hospitals and wondering how they will be able to save enough not only for a new baby in their lives, but also for the costs of the labour and birth. Unfortunately, apart from monthly health care access information sessions, Médecins du Monde is not in a position to take over responsibility for pregnancy follow-up and delivery, and is powerless to meet the needs of these women, many of whom end up in extremely difficult positions. It is completely unjust and discriminatory for these financial obstacles to come between them and access to essential medical care.

The nurses at Médecins du Monde have noticed that many women do not have adequate medical attention, even in high-risk pregnancy cases. They arrive at the hospital at the last minute, leave the premises as soon as they are physically able, and even run the risk of giving birth with no medical attention at all. Labour and childbirth is a nerve-wracking experience even in ideal circumstances; when health care accessibility issues are thrown into the mix, the health risks increase for both mother and child.

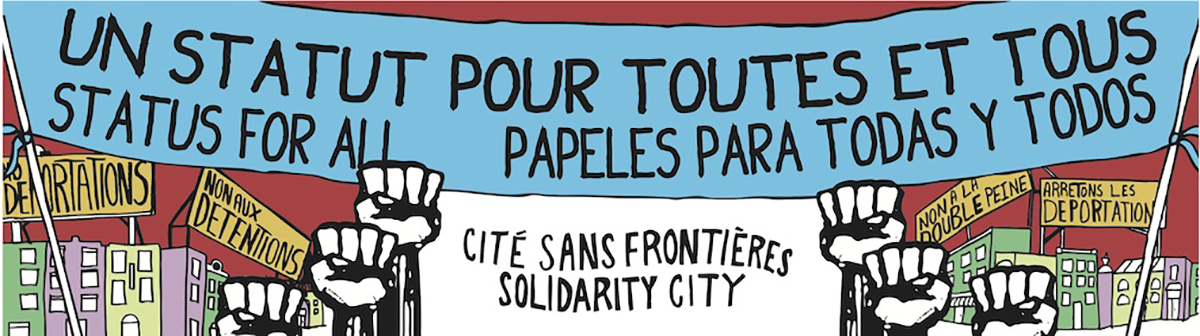

It is a cause for extreme concern that thousands of women are excluded from essential health care services in a country as rich as Canada, where the right to health is said to be universal. In fact, access to health care—and especially maternal health care—should be a fundamental right, independent of immigration status. Like sex, age, ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation, we believe that legal status should not be a discriminating factor when it comes to access to health care.

Médecins du Monde and the clinic for migrants with precarious status

For over ten years now, Médecins du Monde Canada has been providing health care services in Montreal to the most vulnerable people in terms of access to public services. Included among them are more and more migrants with unstable immigration status: these people do not have medical coverage and are unable to pay for health care. Médecins du Monde believes that everyone should have access to health care, regardless of their immigration status.

To meet these increasing needs, Médecins du Monde has started a frontline clinic—the only clinic in Quebec specifically for migrants with precarious status. Since opening in September of 2011, the clinic has provided hundreds of migrants without medical coverage health care that would not be accessible to them through public health services. This clinic benefits from the support and collaboration of many volunteers (doctors, but also social work interns and volunteer orientation workers) that welcome migrants without medical coverage and offer them free confidential health services and referrals.