On December 15, 2012, the federal government proceeded with the implementation of Bill C-31. Dubbed the Refugee Exclusion Act, this legislation establishes a two-tiered refugee determination system that discriminates against migrants on the basis of their nationality. Claimants who are coming from a country included on an arbitrarily-declared list of “Designated Safe Countries of Origin” will see their claims fast-tracked towards deportation, their recourse to legal avenues such as Humanitarian and Compassionate applications restricted, and access to the Refugee Appeals Division denied. In addition, Bill C-31 establishes specific rules, invoked at the discretion of the Immigration Minister, for migrants arriving in Canada by “irregular” means, including mandatory detention with fewer opportunities for review and severely restricted opportunities for permanent residency thereafter. Taken together, these provisions are likely to drastically increase the number of migrants facing detention in the coming years.

The threat of detention and deportation is nothing new to migrants and refugees in Canada: non-citizens always face the threat of potentially indefinite detention by the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA). Although the changes brought about by Bill C-31 are significant and ominous – and promise to wreak havoc in the lives of the migrants and refugees they’ll affect – it’s important to remember that they don’t represent a major break with the traditional practices of Canada’s immigration security regime. Rather, we need to recognize these changes as an escalation – albeit a sharp one – of the kinds of tactics that have been deployed against migrants and refugees for decades, and as part of an ongoing movement towards the increased concentration of arbitrary power in the hands of government ministers and their appointees. This is essential for an understanding of the racist logic underlying the ideology of Immigration Canada, and of the economic interests that influence such policy decisions.

Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, CBSA may arrest and detain a foreign national or permanent resident they deem a threat to public safety, a potential flight risk, unable to substantiate their identity, or a threat to “national security.” Despite the regular invocation of migrants as potentially dangerous and as “criminal,” in reality the overwhelming majority of detainees (94.2%) are held for reasons entirely unrelated to questions of security. Indeed, entire families, including young children, are currently imprisoned in Canadian detention centers. Though detainees are entitled to a review of their detention within 48 hours of their arrest, another 7 days later and then every 30 days after that, the law allows for indefinite periods of such detention. Some migrants languish for months or even years in Canadian detention centers, sometimes based on charges as arbitrary and superficial as invalid travel documents.

With the implementation of Bill C-31, migrants arriving via so-called “irregular” means – arbitrarily applicable to migrants arriving in groups of two or more, or whom the minister otherwise deems unable to be evaluated in a “timely manner” – will face mandatory detention. Under these provisions, detainees may be held for a minimum of a year unless ordered released by a review hearing – which, in these cases, is only required after 15 days, and every six months after that. Even if detainees` refugee claims are subsequently accepted, their pathways to permanent residency are considerably narrowed, as they will be unable to file an application for permanent residency for a minimum of five years. Moreover, such detainees will also be barred from sponsoring their family members for a five-year period.

The most extreme mechanism for the detention of non-citizens in the Canadian immigration security apparatus is the Security Certificate. Security Certificates are used to indefinitely hold ostensible threats to national security under draconian conditions, based on secret evidence not made available to the detainee or to their supporters. Mohammad Mahjoub, Mahmoud Jaballah and Mohamed Harkat have all faced detention on Security Certificates for over a decade. Numerous legal challenges to the Security Certificate system have revealed it to be deeply flawed, often relying on spurious evidence, hearsay or on testimony obtained under torture. However, though the Supreme Court has ruled Security Certificates unconstitutional, it has allowed for their continued use, provided the government amends the practice to include some minimal protections for the accused.

At present, there are three designated immigration detention facilities in Canada. The largest, the Laval Immigration Holding Centre, sits in an open field flanked by several federal prisons and can accommodate up to 150 detainees on any given day. Detention centers are sites of chain-linked fences and constant surveillance, where migrants are subject to prison-like conditions: rigid rules, regimented schedules, restrictions to freedom of movement, and no access to mental health or support services. Detainees are shackled and hand-cuffed when transported to hearings and appointments. Translation services are minimal and access to critical legal support is limited, which frequently jeopardizes claims and applications. This is a far cry from Immigration Minister Jason Kenney’s description of an immigration detention facility as “a three-star hotel with a fence around it.”

Over the past decade, we have witnessed a steady increase in the number of migrants who have been detained. From 2004-2011, an estimated 82000 migrants were detained by Immigration Canada, with an additional 13000 since 2011 alone. This is already too many for the designated immigration detention facilities to handle, and currently as many as 35% of CBSA detainees are held in provincial prisons across the country – exposing them to the dehumanization and likelihood of abuse that are fundamental to the criminal incarceration system. Indeed, a Global Detention Report published in 2012 noted that migrants are currently held in 43 provincial prisons across the country – many of them high-security facilities where detainees are unable to leave their cells for up to 18 hours a day. With the increase in detentions expected in the wake of Bill C-31, we will certainly see this trend continue apace, but recent events also signal another disturbing development: the privatization of immigration detention.

In recent months, many have questioned the extent to which mandatory detention policies are being fuelled by the interests of private companies, who stand to profit enormously from the expansion of the immigration detention system. Indeed, it is already a multi-million dollar industry, and one that is rapidly expanding: it is estimated that more than $53,775,000 is spent annually on immigration detention in Canada. This figure does not account for the costs involved in the surveillance and supervision of migrants, namely of security certificate detainees, which would drive this estimate higher.

Private companies already benefit significantly from their involvement in managing, operating, and providing services in immigration detention centers. Toronto’s Immigration Holding Centre is managed by the Corbeil Management Corporation, and receives security services from G4S, the world’s largest security firm. G4S has recently come under fire for botching a £284m contract to handle security during the 2012 London Olympics and for its complicity in the abuse of Palestinian prisoners through its operation of the Israeli Prison Service. It is estimated that these two companies were awarded more than $19 million in contracts from the federal government between 2004 and 2008. In Montreal, security services at the Laval Immigration Holding Centre are provided by Garda Security.

This trend – putting the management of federal detainees into private hands – is clearly in line with the neoliberal ideology of the current Conservative government, who for the past several years have been quietly studying privatized prison arrangements in other countries. In October 2011, the consulting firm Deloitte et Touche was commissioned to study prisons in ten countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States. A 1400-page report was published in March 2012, assessing each prison and providing recommendations regarding their “relation to Correctional Services Canada” and their “relevancy to the Canadian market”. While Public Safety Minister Vic Toews was quick to deny that private prison models were being considered, he noted that the government was open to private-sector involvement, arguing that private services were already being offered in prisons.

Similarly, in a report issued in 2010, the CBSA recommended resorting to private corrections companies to oversee the operation of immigration detention centres. Immigration Minister Jason Kenney has also signaled his interest in pursuing such arrangements for the handling of immigration detainees. In October 2010, he visited two Australian detention facilities run by Serco (one of the biggest players in the international detention industry) as part of a so-called “fact-finding” tour to examine Australia’s “human-smuggling” initiatives. Not long thereafter, in April 2011, detainees rioted at the Serco-run Villawood center to speak out against their indefinite detention; while a month prior another protest initiated by refugee claimants at Serco’s offshore facility on Christmas Island led to several buildings being burned to the ground. Following his visit, Kenney reportedly tweeted that he had “learned a lot”.

Since the tabling of Bill C-31, a number of private companies have seen the potential for the expansion of Canada’s detention infrastructure, and have been actively lobbying the federal government concerning contracts for the delivery of such services. These include Serco, and BD Hamilton and Associates, a Toronto-based boutique real estate firm, who proposed a public-private partnership to build a new detention center in Toronto. While the BD Hamilton proposal was eventually rejected, the company continues to court the government for contracts related to the “escorted removals” process.

In March 2012, Serco executives travelled from the United Kingdom to meet with Rick Dykstra, Parliamentary Secretary to the Immigration Ministers. While Dykstra quickly dismissed claims that the meeting related to questions of immigration detention specifically, he noted that Serco had never before “had the opportunity to speak with officials about the services they provide from an immigration and citizenship perspective”. He further mused that the meeting could serve to “broaden our horizons about the services they have to offer, to see if there’s a way in which somewhere down-the-line they could assist the Canadian government.”

Yet a “fact-finding” look at privatized detention in other countries should prove to be a cautionary tale. Both the United States and the United Kingdom have witnessed a staggering increase in the proportion of detention services being run for profit. Private companies now operate 7 out of 11 detention centers in the United Kingdom, while nearly 50% are in private hands in the United States. During this time, immigration detention reached record highs. Unsurprisingly, a number of reports have suggested that abuses are widespread, and accountability minimal in for-profit facilities.

In the United States, migrant justice activists have pointed to instances of mistreatment and denial of access to health services in centers operated by CCA and the GEO Group. Geo Group is also currently the subject of a class-action lawsuit, following allegations of sexual abuse in its youth prison facilities, along with its refusal to provide health care or education services to detainees. In Australia, government inspection reports of Serco facilities have cited conditions of dangerous overcrowding, poorly trained staff, rampant neglect and abusive use of solitary confinement.

Clearly, increased cooperation between immigration policy-makers and private corporate interests is on the table, and it is difficult not to see the influence of such cooperation in policies like Bill C-31. Such measures are bound to generate a significant increase in the number of detainees held by the CBSA, all in the name of increased efficiency and “fairness”. Meanwhile, the current infrastructure designated for the accommodation of detainees is already unable to keep up with the influx of migrants into the system. As that demand increases, we can expect to see a greater proportion of immigration detainees placed in provincial prison systems on one hand, and to be told that further privatization is the only solution, on the other.

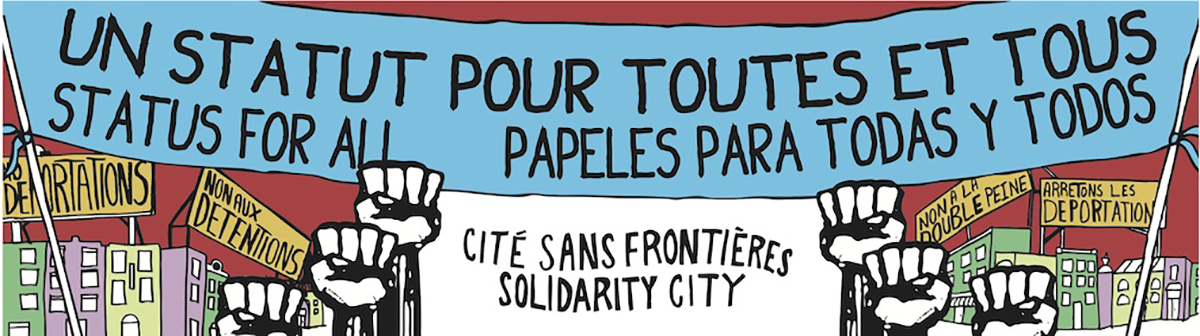

In many respects, the forces of international capitalism and imperialism place migrants and refugees at the nexus at which prison expansion, neoliberal privatization, and the racist violence of the Canadian immigration security apparatus intersect. As such, the various mechanisms for their detention need to be contextualized within this reality. However, the struggle against the detention of migrants and refugees can also serve as a convergence point for diverse movements in opposition to these forces. We continue to resist the criminalization of migration, and work towards a world where the free movement of people takes precedence over corporate profit.